Flying ace

| Flying ace | |

|---|---|

|

|

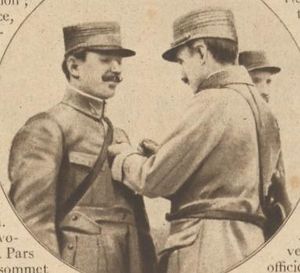

| The "first ace", Adolphe Pegoud being awarded the Croix de Guerre |

A flying ace or fighter ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down several enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The actual number of air victories required to officially qualify as an "ace" has varied, but is usually considered to be five or more.

Contents |

History

World War I

Use of the term ace in military aviation circles began in World War I (1914–18), when French newspapers described Adolphe Pegoud, as l'as (French for "the ace") after he became the first pilot to down five German aircraft. The term had been popularized in prewar French newspapers when referring to sports stars such as football players and bicyclists. This is the reason why "ace" is also used to refer to non-aviators who have distinguished themselves by sinking ships and destroying tanks.

The German Empire instituted the practice of awarding the Pour le Mérite ("Der blaue Max"/"The Blue Max"), its highest award for gallantry, initially to aviators who had destroyed eight Allied aircraft.[1] The Germans did not use the term 'ace', but referred to German pilots who had achieved 10 kills as Überkanonen (big guns) and publicised their names and scores for the benefit of civilian morale. Qualification for the Pour le Mérite was progressively raised as the war went on.[1]

In 1914–16, the British Empire did not have a centralised system of recording aerial victories; in fact, this was done at only squadron level throughout the war. Nor did they publish official statistics on the successes of individuals, although some pilots did become famous through press coverage.[1]

In 1914–18, different air services also had different methods of assigning credit for kills. The German Luftstreitkräfte credited "confirmed" victories only for enemy planes assessed as destroyed or captured after either examining the enemy aircraft (or what was left of it) on the ground, or the capture or confirmed death of enemy aircrew. Any one of these tests seems to have been accepted - for instance the shooting down of Albert Ball was credited to Lothar von Richthofen after his death was confirmed by the British, although the wreckage of Ball's S.E.5 was in fact never identified, and Richthofen's claim was actually for a Sopwith Triplane. Most aerial fighting was on the German side of the lines, so this quite rigorous system worked reasonably well for the Germans themselves, but would have been totally impractical for the Allies, especially the British, who fought mostly in enemy airspace.

Another feature of the German system was that where several pilots attacked and destroyed a single enemy, only one pilot (often the formation leader) was credited with the kill. Most other nations adopted the French Armee de l'Air system of granting full credit to every pilot or aerial gunner participating in a victory, which could sometimes be six or seven individuals. The British were inconsistent in this regard - sometimes a "kill" would be credited to the pilot who got in the closest shot, approximating the German system - more often shared claims were credited to everyone responsible, but apparently sometimes as "shares" rather than "whole" victories. In one instance, a Royal Flying Corps pilot described his own score in a letter to his wife as "Eleven, five by me solo - the rest shared". He went on to say, "so I am miles from being an ace".[2]. It appears that his unit, at least, counted "shared" and "solo" victories separately. That pilot, who later became an air vice marshal, is not mentioned in the list of British aces, so some of his "solo" kills may not have been officially confirmed.

In the Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service or Royal Air Force, pilots were required to write 'Combat Reports' for each engagement with the enemy, and after review by their squadron commander, these were sent to Wing Headquarters. In the jargon of these reports, a victory claim was called a "decisive combat". The Wing Commander allowed or disallowed each claim, but then passed them on to Brigade (Group) HQ, which also reviewed the reports. By 1918, it was clear Wing HQ did take considerable care to reduce duplication and inaccuracies within these reports. The main weakness however was the lack of a central verification and review process.

British or Commonwealth pilots on offensive patrol many miles over the German lines were often not in a position to confirm that an apparently destroyed enemy aircraft had in fact crashed, so that victories were frequently classified as "driven down", "forced to land", or "out of control" - what would be called "probables" in later terminology. They were however usually included in a pilot's official totals in (for instance) citations for decorations.[3] The United States Army Air Service followed a similar practice. For example, Eddie Rickenbacker's 26 official victories included ten planes "out of control" and several "dived east". Even allowing for possible modest understatement, these would (at best) have been credited as "probables" in later wars.

While "ace" status was generally won only by fighter pilots, several bomber and reconnaissance crews on both sides also destroyed some enemy aircraft, typically in defending themselves from attack. An example is an action on 23 August 1918, in which the Bermudian pilot, Lieutenant Arthur Spurling claimed the destruction of three D.VIIs with his DH-9's fixed, forward-firing machine gun, while his gunner Sergeant Frank Bell claimed two more with his rear gun. Spurling was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, largely on the strength of this action.

World War II

In World War II, many air forces adopted the British practice of crediting fractional shares of aerial victories, resulting in fractions or decimal scores, such as 11½ or 26.83. Some U.S. commands also credited aircraft destroyed on the ground as equal to aerial victories. The Soviets distinguished between solo and group kills, as did the Japanese, though the Imperial Japanese Navy stopped crediting individual victories (in favor of squadron tallies) in 1943. The Luftwaffe continued the tradition of "one pilot, one kill", and now referred to top scorers as Experten.[4]

The Soviet Air Force had the world's only female aces. During World War II, Lydia Litvyak scored 12 victories and Katya Budanova achieved 11.[5] Pierre Le Gloan (France) had the unusual distinction of shooting down four German, seven Italian and seven British planes, the latter while he was flying for Vichy France in Syria.

For a certain period (specially during Operation Barbarossa), many Axis kills were over obsolescent aircraft and either poorly-trained or inexperienced Allied pilots, especially Soviet ones.[6] In addition, Luftwaffe pilots generally flew many more sorties (sometimes up to 1000) than their Allied counterparts. Additionally, Axis pilots tended to return to the cockpit over and over again until they were killed, captured or incapacitated, while successful Allied pilots tended to be either promoted to positions that involved less combat flying, or routinely rotated back to training bases to pass their valuable combat knowledge to younger pilots.

Accuracy

Realistic assessment of enemy casualties is important for intelligence purposes,[7] so most air forces expend considerable effort to ensure accuracy in victory claims. In World War II, the aircraft gun camera came into general usage, partly in hope of alleviating inaccurate victory claims.

And yet, to quote an extreme example, in the Korean War, both the U.S. and Communist air arms claimed a 10 to 1 victory-loss ratio.[8][9] Without delving too deeply into these claims, they are obviously mutually incompatible. Arguably, few recognized aces actually shot down as many aircraft as credited to them.[10] The primary reason for inaccurate victory claims is the inherent confusion of three-dimensional, high speed combat between large numbers of aircraft, but competitiveness and the desire for recognition (not to mention sheer optimistic enthusiasm) also figure in certain inflated claims, especially when the attainment of a specific total is required for a particular decoration or promotion.[11]

The most accurate figures usually belong to the air arm fighting over its own territory, where many wrecks can be located, and even identified, and where shot down enemy are either killed or captured. It is for this reason that at least 76 of the 80 planes credited to Manfred von Richthofen can be tied to known British losses[12] — the German Jagdstaffeln flew defensively, on their own side of the lines, in part due to General Hugh Trenchard's policy of offensive patrol.

On the other hand, losses (especially in terms of aircraft as opposed to personnel) are sometimes recorded inaccurately, for various reasons. Nearly 50% of RAF victories in the Battle of Britain, for instance, do not tally statistically with recorded German losses - but some at least of this apparent over-claiming can be tallied with known wrecks, and aircrew known to have been in British PoW camps.[13] There are a number of reasons why reported losses may be understated - including poor reporting procedures and loss of records due to enemy action or wartime confusion.

Non-pilot aces

While aces are generally thought of exclusively as fighter pilots, some have accorded this status to gunners on bombers or reconnaissance aircraft, and observers/rear gunners in two-seater fighters such as the Bristol F.2b. World War II United States Army Air Forces B-17 tail gunner Michael Arooth is credited with 17 victories, while in World War I, observer John Rutherford Gordon tallied 15. Because pilots usually teamed with differing observer/gunners in two-seater aircraft, an observer might be an ace when his pilot was not, or vice versa. Observer aces are a sizable minority in the lists.

With the advent of more advanced technology, a third category of ace appeared. Charles B. DeBellevue became not only the first U.S. Air Force Weapons Systems Officer (WSO) to become an ace, but also the top American ace of the Vietnam War, with six victories.[14] Close behind with five were fellow WSO Jeffrey Feinstein and Radar Intercept Officer William P. Driscoll.

Ace in a day

The term "ace in a day" is used to designate a fighter pilot who has shot down five or more airplanes in a single day. The most notable is Hans-Joachim Marseille of Germany, who was credited with downing 17 Allied fighters in just three sorties over North Africa on September 1, 1942, during World War II. The highest number aerial victories for a single day was claimed by Emil Lang: 18 Soviet fighters on November 3, 1943. Erich Rudorffer is credited with the destruction of 13 aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. Numerous other Luftwaffe pilots also claimed the title during World War II.

Captain Hans Wind of HLeLv 24, Finnish Air Force, scored five kills in a day five separate times during the Soviet Summer Offensive 1944, a total of 30 kills in 12 days, of his final tally of 75.

On December 5, 1941, the leading Australian ace of World War II, Clive Caldwell, destroyed five German aircraft in the space of a few minutes, also in North Africa. He received a Distinguished Flying Cross for the feat.

During World War II, 68 U.S. pilots—43 Army Air Forces, 18 Navy, and seven Marine Corps—were credited with the feat, including David McCampbell, who claimed seven Japanese planes shot down on June 19, 1944 (during the "Marianas Turkey Shoot"), and nine in a single mission on October 24, 1944. Medal of Honor recipients Jefferson DeBlanc and James E. Swett became aces on their first combat missions in Guadalcanal, scoring five kills and seven kills respectively. US Navy pilot Stanley "Swede" Vejtasa, who during the Battle of the Coral Sea shot down three Mitsubishi A6M Zeros with a Douglas SBD Dauntless, managed to down seven Japanese planes in one sortie in the Battle of Santa Cruz flying a Grumman F4F Wildcat.

World War I flying ace Fritz Otto Bernert scored five victories within 20 minutes on April 24, 1917, even though he wore glasses and was effectively one-armed. This earned him the Pour le Merite award.

The world's top Mustang ace, George Preddy, shot down six Me-109s on August 6, 1944, setting the European Theater of Operations record.

See also

- List of World War II aces by country

- List of Spanish Civil War air aces

- List of Korean War air aces

- List of Vietnam War flying aces

- List of flying aces in Arab-Israeli wars

- List of aces of aces

Sources

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dr David Payne (21 May 2008). "Major 'Mick' Mannock, VC :Top Scoring British Flying Ace in the Great War". Western Front Association website. http://www.westernfrontassociation.com/great-war-at-sea-in-air/the-aces/283-mick-mannock.html.

- ↑ Lee, Arthur Gould, No Parachute, London, Jarrolds, 1968 p. 208

- ↑ Shores, Franks & Guest, Above The Trenches, 1990, page 8

- ↑ For the award of decorations, the Germans initiated a points system to equal up achievements between the aces flying on the Eastern front with those on other, more demanding, fronts: one for a fighter, two for a twin-engine bomber, three for a four-engine bomber; night victories counted double; Mosquitoes counted double, due to the difficulty of bringing them down. See Johnson, J. E. "Johnnie", Group Captain, RAF. Wing Leader (Ballantine, 1967), p.264.

- ↑ Bergström, Christer (2007). Barbarossa - The Air Battle: July-December 1941. Classic Publications. p. 83. ISBN 1857802705.

- ↑ Shores, Christopher (1983). Air Aces. Bison Books Corp.. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0861241045.

- ↑ The classic instance of this is the catastrophic failure of German intelligence to accurately assess RAF losses during the Battle of Britain - due (in large part anyway) to wild over-claiming by German fighter pilots

- ↑ http://wio.ru/korea/korea-a.htm

- ↑ Shores pp. 161-167

- ↑ See for example the analysis by Christopher Shores 2007 online at the Japanese and Allied air forces in the Far East forum

- ↑ Hermann Goering - quoted by Galland, 1956: p. 279. Goering actually goes much further, and claims that scores were deliberately falsified for the purpose of fabricating grounds for decorations - but this seems unlikely to be the case, nor Goering's real opinion.

- ↑ Robinson 1958, pp. 150–155

- ↑ Lake P 122

- ↑ "Col. Charles DeBellevue". U.S. Air Force official web site. http://www.af.mil/information/heritage/person.asp?dec=&pid=123006474. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

References

- Hobson, Chris. Vietnam Air Losses, USAF, USN, USMC, Fixed-Wing Aircraft Losses in Southeast Asia 1961–1973. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-1156.

- Galland, Adolf The First and the Last London, Methuen, 1955 (Die Ersten und die Letzten Germany, Franz Schneekluth, 1953)

- Johnson, J. E. "Johnnie", Group Captain, RAF. Wing Leader (Ballantine, 1967)

- Lake, John The Battle of Britain London, Amber Books 2000 ISBN 1-85605-535-3

- Robinson, Bruce (ed.) von Richthofen and the Flying Circus. Letchworth, UK: Harleyford, 1958.

- Shores,Christoper Air Aces. Greenwich CT., Bison Books 1983 ISBN 0-86124-104-5

- Stenman, Kari and Keskinen, Kalevi. Finnish Aces of World War 2, Osprey Aircraft of the Aces, number 23. London: Osprey Publishing. 1998. ISBN 952-5186-24-5.

- Toliver & Constable. Horrido!: Fighter Aces of the Luftwaffe (Aero 1968)

- Toperczer, Istvan. MIG-17 and MIG-19 Units of the Vietnam War. Osprey Combat Aircraft, number 25. (2001).

- _________. MIG-21 Units of the Vietnam War. Osprey Combat Aircraft, number 29. (2001).

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||